In this post, we return to the topic of politics in projects. Politics has a bit of a dirty name. It’s associated with false promises, backstabbing, alliances and manipulating others. The worst weakness of Politics is its failure to deliver on its promises. Time and time again we see public politicians or business leaders failing to deliver the change they promise. Yet, as project managers everything we do involves change. Be it change in the physical environment (such as building new houses), in the processes and systems organisations use (such as introducing new IT systems) or in the behaviours in a culture (such as improving customer service).

Inevitably people have expectations and views on these planned changes. Some may be advocates, some may be vehemently opposed, some may not have formed an opinion yet. These views and attitudes have a significant impact on the success of a project. Delivering a project in the face of strong opposition is almost impossible, and even the smallest project (such are re-arranging where people sit in an office) can stir up strong emotions.

Delivering a project in the face of strong opposition is almost impossible and even the smallest project (such are re-arranging where people sit in an office) can stir up strong emotions.

The challenges don’t just come from outside the project; often a project brings together different teams or organisations, each with different objectives. These teams can have very diverse cultures and attitudes. For example, a operations team may see change as a threat to the way they currently work or they may be overloaded with day-to-day demands which mean the project is a distraction from the real work of the department or function. External suppliers too may have very different motives. They may want to maximise short term profits, or they may have over-committed their resources to too many contracts.

These internal and external attitudes and mixed expectations are very powerful forces, which can destroy the collaboration and cooperation needed to deliver a successful project. This is why most people agree that managing people and developing teamwork are the most important part of a successful project

The Politically Astute Project Manager?

Many people would argue that projects and project managers should ignore politics and focus on getting the job done. They say that project management is a set of processes to produce deliverables that enable change, and the project manager should not get involved in internal or external politics. However, if you ask the same people why projects fail they typically give the following reasons:

- The project lacked senior management support.

- The project was under-resourced.

- The project brief (or design) is not developed early enough.

- There were too many uncontrolled changes.

- The users didn’t use the products in the way expected (if at all).

- The project was not planned properly.

- The budget was insufficient to meet the expectations.

Why do these things go wrong with projects?

If senior management are not convinced about the priority of a project, they are reluctant to commit the necessary resources.

If the project fails to inspire users, they don’t engage with the project early.

If functional managers perceive the projects as a low priority, they are reluctant to support the project with sufficient resources or time.

If the senior management in the customer and supplier organisations don’t understand each other’s objectives, they don’t work together, which makes commercial issues more difficult to resolve.

All these issues relate to the degree of support for the project, within the individual and organisations involved. To be successful a politically astute project manager will manage these issues by developing a simple uniting project rationale, working hard to win the support of senior management, building alliances and coalitions with users, functional managers and suppliers and uniting the project team around a common purpose. This does not mean we can forget everything else we have learned about project management we just need to view it from a political perspective.

To be successful a politically astute project manager will manage these issues that by developing a simple uniting project rationale, working hard to win the support of senior management, building alliances and coalitions with users, functional managers and suppliers and uniting the project team around a common purpose.

Effective Governance and Sponsorship

At the start of a project, most teams are keen to get the ball rolling and get going as soon as possible. All too often we don’t take the time to think about the governance and sponsorship arrangements. For many these seem like theoretical and challenging concepts that have little relevance to the reality of project delivery. Then part way through the project, reality strikes and we realise that the project budget and timescales are insufficient to meet the expectations of the users. The expectations for the project often exceeded the resources to deliver or the capacity to change in the organisation. At this stage we really do need the support of senior managers to take some critical decisions, typically these include:

- Which parts and elements of this project are vital for the organisation’s strategy and which parts, if any, are optional?

- Who is ultimately responsible for the decisions associated with the project, who has authority to prioritise the expected benefits and modify the scope?

- Who in senior management will act as an advocate for the project and influence senior stakeholders during the decision-making process?

- How important is this project in the overall portfolio? Can we divert resources from other projects or operations to support this project?

- Who will ensure that the project team has the right levels of competence and capability to deliver the project?

These are all critical decisions that need to be taken by senior management as part of the governance and sponsorship process.

The Role of Governance in Project Motivation

Have you ever worked on a project in which critical decisions were not taken promptly or even worse change after the fact? Then you will know how demotivating this can be. The motivation of a project team is challenging at the best of times, but when there is a lack of direction or leadership, then motivation suffers.

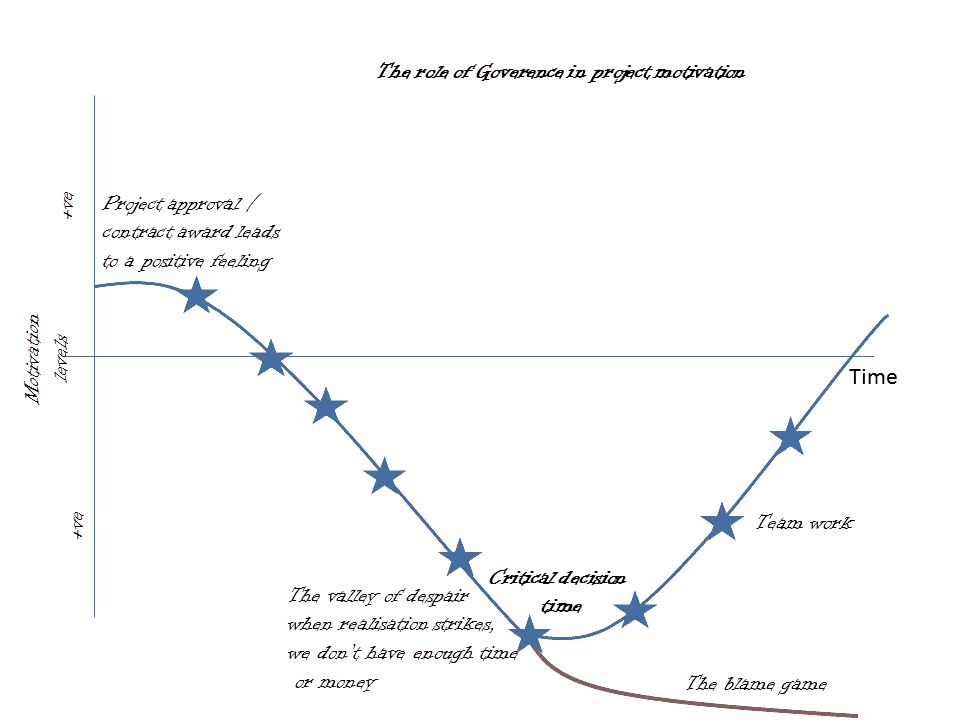

Governance and sponsorship has a vital role in this decision-making process, but as we can see in figure 1, we have to establish the governance framework early in the project. Most projects start with a reasonable level of motivation; we have either been awarded a contract or funding has been approved and the project we have been working on for months (even years) is suddenly a reality.

Now is the time to establish the governance arrangements, we need to get the project board (or steering group) appointed and taking ownership of the key decisions while things are going well. This is because the good times generally won’t last, it will soon emerge that the project is more complex, challenging and difficult than we envisaged. Unexpected difficulties will arise, resources that we expected may not be available, and the uses may not be clear what they want. There are good reasons why this happens rooted in the fact that we need to minimise the costs, and a competitive bidding process is biased towards the lowest price and our inherent optimism.

At this point, the project team enters the valley of despair, and we have two options; teamwork or the blame game. We can either take some hard decisions and have tough conversations with the users because they may not get everything they imagined or hoped for, in which case the project may be united to achieve a positive result. Alternatively, the team enters a blame game, in which everyone subconsciously accepts that the project will fail and tries to limit the damage to themselves (personally and commercially) by working in their individual interests.

Clearly, teamwork and a successful result is preferred, but these decisions need the support and teamwork from senior management. Compromise will be required from:

- Users because they may not get their full requirements

- Funders because the may have to find some more cash

- The project team because they may need to compromise on the perfect solution

- Suppliers because they may have to carry some of the pain and inconvenience

Governance and sponsorship are vital here, to re-focus everyone on the benefits and the strategy. Why are we here and what is this project ultimately trying to achieve? What baggage can we jettison to achieve the ultimate goal?

Politically astute project managers spent time establishing this governance and sponsorship framework at the very start of the project, so that the senior management is inculcated in the decisions along the way; otherwise they may get interested just as the project hits the valley of despair and start looking for people to blame.

This is the valley of despair and at this stage we have two options, team working or the blame game.

Practical Hint’s and Tips on Governance and Sponsorship

A politically astute project manager recognises the criticality of effective governance and sponsorship to project success and will take the following steps:

Names are very important; for example a project board sounds more like an effective decision taking body than a project steering group.

Decide and establish governance arrangements early in the project

At the beginning of the project, the politically astute project manager determines the most appropriate governance arrangements. Names are paramount; for example, a project board sounds like a more effective decision-making body than a project steering group. However, they may need to work within the constraints of the organisation’s framework and naming conventions; with the aim of getting the best possible arrangements. A politically astute project manager does not leave the governance arrangements to chance, they proactively engage with the governance arrangements of the organisation to make sure the project board has the time to commit to the project, has enough authority to take the necessary decisions and has active communication channels to senior management.

Who Should be on the Project Board

The chair of the project board needs careful consideration. It is often tempting to ask the most senior managers to act as the project sponsor and chair of the project board. However for all but the most mission-critical projects it is unlikely they will have the time necessary to dedicate to the project. So it may be prudent to ask the senior managers to delegates responsibility to a trusted individual who can act on their behalf. Some organisations call this a sponsor’s agent. The are trusted by the senior management to take the necessary actions and consult with senior management when critical decisions are required. A politically astute project manager will always seek to secure the most active sponsor for the project.

Likewise, the politically astute PM will often want input from users and suppliers into the decision taking process and governance. The select users who have the ability and time to understand how the products produced by the project (be it a building, IT system or piece of infrastructure) will be used in the future. This can be difficult if the users also have a day job, especially in organisations operating at capacity or with 24/7 operations with shift patterns or agencies that are building new assets that don’t have an operational team yet. An example of this might be a new school, railway or power station, where the operations staff may not be in post until the end of the project. The politically astute PM goes out of their way to get user input into the project. Options include back-filling operations positions with temporary staff to release the necessary user resources or to establish a shadow operations team for a new asset. This is because they know that operational user knowledge of the project deliverables is vital to a successful project.

Good suppliers with the right competence and attitudes are vital to the success of many projects. The politically astute project manager knows that conflict will occur between the needs of the supplier to make a decent profit and the needs of the project, especially in the depths of the valley of despair. They will establish communication and escalation mechanisms early on so they can address potential issues as and when they arise. They predict the needs of suppliers and stay ahead of potential contractual issues. They will build bridges with the senior management in the supplier organisation, providing an escalation route to resolve contractual issues without recourse to the courts.

Establish Links to Corporate Governance

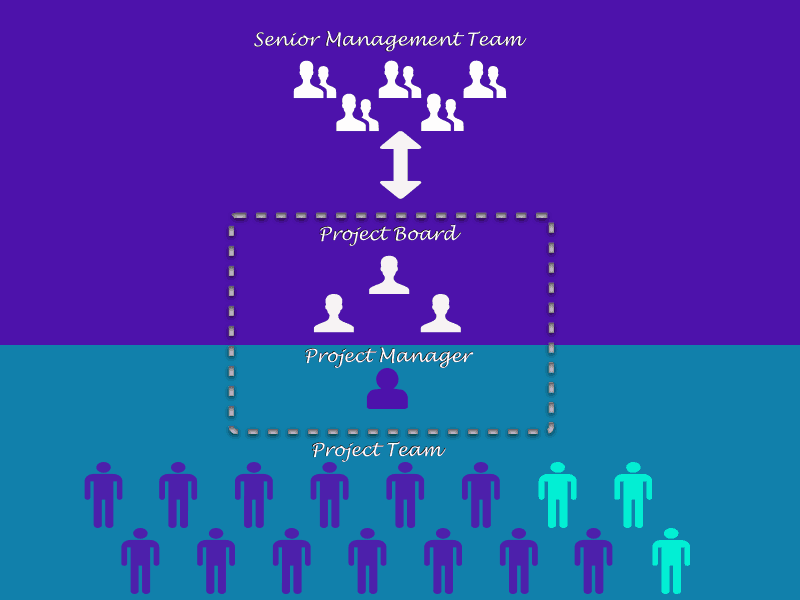

Project do not happen in isolation, they often involve several organisations, each of which has its own internal politics. This conflict of internal politics of different organisations presents many challenges for the naïve project manager. The politically astute project manager will have recognised internal politics and set out to use the internal governance arrangements to manage the communications and expectations of the senior management team. They will work with senior managers to establish the reporting requirements and who needs to take what decisions. For example who needs to approve the funding for the project? Who can approve changes? What reports are required by senior management? As you can see in figure 2 below the project board acts as the bridge between the project management team and the senior managers in the organisation.

Talk the Language of the C-suite

Political project managers know that when working at an executive level (CEO or COO) they need to operate at a strategic level. Language is very important in the way they communicate. They avoid project management jargon and use language which has meaning to the audience. For example, the time to market; not the project schedule, return on investment; not costs, return on investment; not benefits. (for more on this see my interview with Mark A. Langley, President and CEO of Project Management Institute.

Planning Strategic Decisions

The political project manager knows that organising project board meetings in response to issues is just impossible. Senior people’s diaries are booked out weeks if not months in advance. Therefore, they plan ahead putting the key meetings in the diaries in advance. They may even provide the project board with a schedule of key decisions they will be required to make during the project, for example they may say to the board “in the January meeting I will expect you to approve the funding” and “in July I will expect you to approve the selection of the contractor“, “at the meeting in August I will be expecting you to decide on which parts of the requirements you are willing to compromise in order to fit within the project constraints” etc. This pre-positions senior managers so that know what is expected, reinforcing their role in the key project decisions and also helps to keep the project on time.

Compelling Business Case

The business case is not just important for the authorisation of the project; it’s also an important way of distilling and communicating the purpose of the project. We all know the story of JFK and the man at NASA cleaning the toilet.

During a visit to the NASA space centre in 1962, President John F. Kennedy noticed a janitor carrying a broom. He interrupted his tour, walked over to the man and said, “Hi, I’m Jack Kennedy. What are you doing?”

“Well, Mr. President,” the janitor responded, “I’m helping put a man on the moon.”

The lesson is: to get the best out of people they need a sense of purpose, it’s not inspiring to go to work to deliver the project to time, cost and quality, but it is inspiring to go to work to improve the education of children, or improving people’s journey to work or providing homes for people with growing families. The political project manager sees developing the business case not as a bureaucratic document, but as a mechanism to build a clear and compelling purpose for the project. Take for example the mission for Crossrail which is the biggest construction project in Europe. It has a simple vision of

Moving London Forward

A simple yet ambitious message unites a highly complex supply chain. For example, the client team of 1,200 people come from nine different employers, and they oversee delivery from twenty principal contractors, each with their own supply chain (total workforce peaks at around 14,000 later this year). The political project manager knows that to be successful, the business case has to survive the elevator pitch (or even the Dragons Den). They know that benefits expressed in a simple and effective way are highly motivational for the project team and key stakeholders. Muddled, confused or poorly communicated aims leave people lost and unsure why the project is important.

Proactive User Engagement

The political project manager knows that they need to develop and maintain a strong relationship with the users. They also recognise that this might be difficult if users have on-going operational roles to fulfil. Despite this difficulty, they take proactive actions to get the users involved in defining and developing the project requirements and making sure they fit with the long-term operation needs of the user. This is especially important if the users are working different shift patterns, are based in different locations or are overworked keeping the existing systems running at capacity whilst the new are developed. They take proactive actions to engage with users, such as funding temporary staff so that operations staff can find the time to support the project, facilitating user requirements workshops to help users think through how they are going to use the outputs of the product or a shadow operations team for a new asset. Without this engagement, it is always too easy for the users to be disappointed that the project fails to meet all their hopes and dreams for the project. This disappointment can lead to delays accepting the output of the project and an extended handover process, with the associated extra costs and delay.

Collaborative approaches to planning

The political project manager knows that most project delays occur because of interfaces between one team and another. To address this, they pay particular attention to scheduling dependencies between different teams and contractors and they avoid micro-planning activities within a team. They also know that it’s important to get work package leaders involved in planning so that they develop a shared understanding of the cross-functional dependencies. For example pulling the design team, contractor and the client together in a meeting to agree on the key dependencies within the project. They avoid over-complex plans, which become difficult to update and maintain. They let the work package managers plan and manage the day-to-day detail, leaving the political manager free to maintain the overall view of the project dependencies and timescales.

Relay Runner Work Ethic

Ask yourself how much time is wasted on the critical path activities in the slow lane, especially early in the project lifecycle. The relay runner work ethic describes a culture in which the critical path deliverables are passed on to the next person as soon as possible. As in a relay race, we make sure the next person in the team has a good hold of the baton before we let go. So in a project context, this means confirming that the next person has started work on the critical path before we let go. This can just be a phone call or brief conversation to confirm that the work has been received and understood before we close out the activity.

Simple but Effective Project Controls

Regular and routine project controls provide a good self-discipline for every project but at some stage, they become too complex and bureaucratic to add value. Plan the work; work the plan is one of the oldest and truest phases in project management. But the political project manager knows that they also have to keep it simple stupid. So the more complex a project control system; the less value it adds to the project. The focus on the minimum number of key performance indicators required to get the job done. They challenge every bit of information collected by asking “what decisions will be taken on the basis of this information”. However they are rigours about applying the project control cycle, progress reports no matter how simple must be completed on time, at a regular and planned interval.

Rigours Change Control

Uncontrolled scope change destroys progress and undermines team morale faster than anything else. It causes doubt confusion and uncertainty in the project team. No one is sure what is going on and which is the correct information. The political project managers proactively manage changes with the senior people from the start, establishing effective decision-making processes to consider and review changes from the outset. This might include a change control board, who have the authority and incentives to take decisions. Too often delay in reaching a decision over change will result in increased cost and further delay to the project. Establishing these decision processes early improved the chances of changes being managed in an effective way.

User Engagement in Handover

All too often the users are not involved in planning handover and acceptance early in the process. This can cause real problems if the project has had to adapt to changes and constraints during the project lifecycle. The political project manager goes to extreme lengths to keep the users engaged in the project and especially in the run up to handover. They make sure that they agree to any compromises and use the authority of the sponsor if necessary to take the hard decision. Avoiding user involvement in these key decisions can seem like it may be saving time during delivery, but will cause extended delays during the handover process.

Great post Paul!

“even the smallest project (such are re-arranging where people sit in an office) can stir up strong emotions”

That is just so true it made me laugh but also I wonder why people are so attached to ‘the way things are’ (the status quo) … I guess we are all just afraid of change in some deep fundamental way and so need to be reassured. That’s why it’s so important to be proactive and collaborate as you suggest

Tom

We all hate change( either physical or organisational), especially if it is being done to us and we are not in control of the change. The more time I spend with project managers the more important I think this political issues are.

This is one great and sincere piece. Having a politically astute project manager helps propell the decision making process and ensure the project survives amid waves of external challenges. This is usually appreciated when implementing a project in a fragile and conflict affected state.

Jasper

Thanks for the feedback, I am glad you found the article useful.

Paul